Introduction

The Motet is a vocal polyphonic form intended for the liturgical sphere: it is therefore a composition of Sacred Music. We Italians memorize and associate this term with difficulty with a liturgical composition, because the contemporary use of the word motto, especially in the Italian language, is associated mostly with mottos of spirit, therefore with jokes or jokes. When we ask someone what your motto is? we expect a sentence in which the program of life of a person or a company, an association, a community is contained …

We must think that in the twelfth century, the year in which the compositional form of the Motet was born, the students and the Troubadours of the Ars Antiqua had much more in mind. We also see it in the different etymology of the two terms Motto and Motet: the first term comes from the vulgar Latin muttum, in the meaning of whispering, while the second from the diminutive of motto in the archaic meaning of poetry, words of a song. In other words, when we say Motet we do not mean a small allusive joke to whisper to our snack companion, but words and music with sacred content organized according to a precise poetic-contrapuntal structure.

Ingres, 1848.

Contrapuntal Techniques

The important question in the analysis phase is to be able to recognize the different contrapuntal techniques of which a given Motet is composed. I list in a table the most important:

| Bicinia Technique | It represents through two-part writing a moment when there are only two voices at play. |

| Homorhythmia | It represents a moment of homorhythmy between the vocal types. |

| Imitation | It represents the repetition of a melodic phrase performed by a voice different from the one that had exposed it the first time. |

| Polychorality | It represents the moment in which the whole organic is divided into one or more vocal groups called semichores. |

| Sesquialtera proportionality | It represents the moment when the composition passes from the binary rhythm to the ternary rhythm in the sesquialtera proportion. |

Practical analysis of a motet

We have said that a Motet has a polyphonic form where multiple voices act without accompanying instruments. Only in the late Baroque, with the Motets of J. S. Bach, we see a Motet for choir and orchestra. In the Renaissance this does not happen. At the time it was not even used to use the score, that is, the set of different voices, but the composer wrote four distinct scores for each of the voices. The overlap, the final result, the composer had in mind. Below I will show you for simplicity the modern transcription of a Motet and on this we will operate a first analysis. The transcription belongs to the editions Les Éditions Outremontaises, 2008 © . It is not excluded that you can find transcriptions of the same piece that report different values or subdivisions of beat because the rhythmic conception of the Music of the times of this Motet was completely different from today's.

False Myths

Of course when we read Bass, Tenor, Alto (or Alto) and Soprano we think of the mixed male and female choir. In fact we must know, before going into the analysis, that there was no such distinction: it was all men who sang and this is why Alto and Soprano are still masculine terms. It will come much later than the practice of women's singing in the sacred liturgical devotional repertoire. The highest voice was usually sung by children, by white voices.

The imitative episode

Among the contrapuntal techniques that we have listed, that of imitation is particularly interesting because it often assumes a compositional function at the macrostructural level: in other words, a Motet can present itself as a set of several Imitative Episodes, in which three of the four voices imitate a model that is usually presented first.

The First Episode

The Motet Ave Maria by Josquin Des Prez, for example, begins with a cascading imitative episode that we could define in catabases: we start from the highest voice and then the second voice takes up the exact same motif at the octave below, then tenor and bass enter.

The Canon

If in an imitation all the voices are strictly equal in their internal interval relationships, it proposes precisely the whole profile of the first reason exposed: in this case we speak of Canon, a term synonymous with Escape. In our example above we see a very rigorous imitative counterpoint procedure between the voices: therefore it is a Canon, and not just any one, but so-called at the octave because the interval ratios are replicated an octave away.

The Octavicized Musical Key

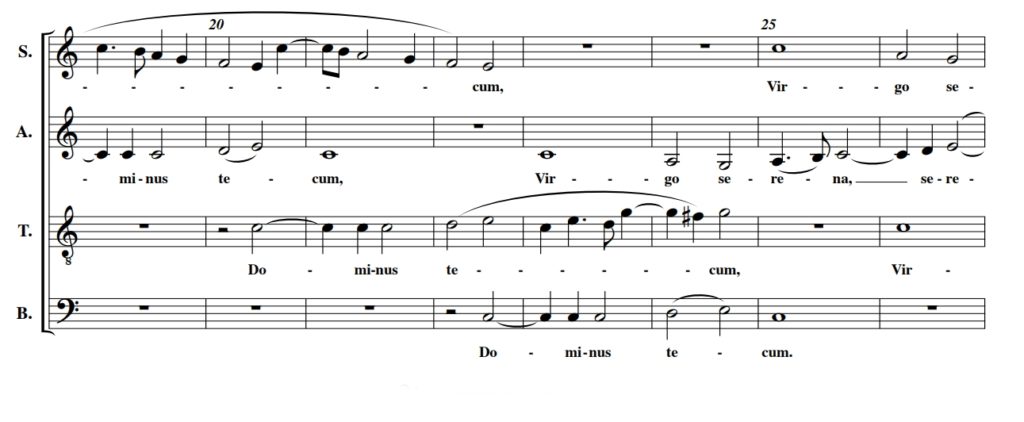

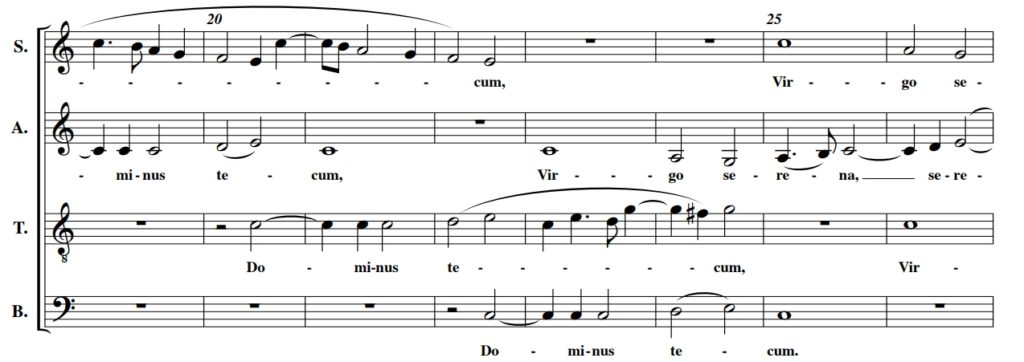

The third voice is written on the upper pentagram, but the violin key is octapitated, so the sol we are talking about to the tenor is in unison with the Alto.

The Second Episode

We can see below that the second episode of the Motet is already much more fluid, for example we still have the Soprano who starts with his melody and the Alto who responds to the octave below.

Here too the interval ratios of the Alto are strictly the same as the soprano but at the octave below and also the third voice is practically identical from an interval point of view, according once again to the scheme of the Canon, but in the fourth voice we see a simplification: the characteristic of the second episode compared to the first is therefore that it begins to be more fluid with smaller values and with a rhythmic articulation of the melody more intense and articulated with respect to the first episode.

The Third Episode

Here, with this third episode, the melody becomes even more flowery and rhythmically articulated.

There is a more extensive vocalization especially we note some very significant peculiarities that are for example the sixth jump which is a very expressive and pathetic jump, the abbreviation of the rhythmic figures that define a more intense compositional skeleton.

The second voice loses its rigorous characteristic of imitation, it is no longer canon, it recalls the initial cue of the soprano and starts with the do retorting it but all the melisma that the soprano did in reality the alto no longer does. Then there begins to be a clear division into semichores: the two upper voices close and the two lower ones appear: this is a first small fragmentation of the choir into two subgroups (semichores). The alto starts with a technique that in counterpoint is very frequent: the episode of tenors and basses is still ending, everything will end only on C grave, but in reality the next episode begins before, virgo serena. This is a contrapuntal fading technique that involves the introduction of a new episode at the end of the previous one: it represents a great element of fluidity of the voices.

The point of maximum density

The voices are all concentrated at bars 28 29 and 30, on the entry of the bass there is the maximum density reached so far. This is the only point where we have the four voices together that are singing simultaneously and on a rather complex rhythmic figuration, on small values: let's look for example at the articulation in the movement of the tenor. At bar 30 we find a cadence on the C, very clear, because we have the feeling that one speech has closed and another is starting.

Additional Considerations

The whole score is based on imitative moments and homorrhythmic moments of the type we have already indicated. In order not to repeat ourselves further, let's make some further considerations: a very interesting aspect of the composition is that each episode, each fragment, has a form of cadence. In the ancient counterpoint we cannot speak of cadences from a harmonic point of view, the term clause is used more generically to indicate the terminal phase of an Imitative Episode. See what happens in this part of the Motet:

In this fragment, at bar 24, there is a collision between the G and the A, a dissonance of the second major that is given by the fact that the sol delays the fa diesis. This harmonic technique is called the delay of the sensitive, something that we usually think belongs only to Modern Harmony but that we now see in reality already being as a typical conventional gesture in the Renaissance: this harmonic technique in the context of the composition that we are examining indicates that when we arrive on the sol with the delay of the sensitive we conclude the expression of a subject and, closed this subject, begins another which in turn has its own clause.

Conclusions

With this practical analysis I hope to have introduced you to a deeper understanding of the compositional technique of Motet. If you want to deepen the discourse on Renaissance contrapuntal techniques, I recommend the most complete text on the subject that I have had the opportunity to read, by the authors Renato Zanolini and Bruno Dionisi: you can find it below. It costs a bit, but it's one of those texts that you can't not have in your library. I leave you to him: see you in the next article!

- History Of The Piano – The Fortepiano - July 12, 2022

- Curt Sachs – History Of Organology At a Glance - July 8, 2022

- Giuseppe Verdi – Rigoletto, Il Trovatore, La Traviata - June 29, 2022