Introduction

The Sonata is among the most debated subjects of Musical Analysis. The most representative monument of this compositional form is certainly the work of L. V. Beethoven, more precisely his 32 Piano Sonatas, composed over a very long period of time: about 27 years. Without continuing along the lines of historical information now available everywhere, in this article I will give you practical information to understand what you can base your analysis of the compositional material of a Sonata.

The Concept of Form

The term Forma in Musica usually indicates a structure based on a whole series of technical-compositional elements: those that are usually exalted in a conventional analysis, among all, are the harmonic-rhythmic elements. This trend, although it represents a possible and valid starting point of the analysis, should be gradually integrated with a structurally broader vision of the musical phenomenon: let's think for example of the concept of Sound that we dealt with in a previous article. Without the necessary integrations, we risk falling into a sterile reductionism: of confusing the Form with the concept of Gender, linked to the social habits of listening… And to run into many other errors that derive from the lack of discernment of the compositional themes usually neglected.

Style VS Gender

Style is the way in which formal needs take shape in a composition, while Gender mostly defines the mode of consumption, the socio-historical-cultural context of a given composition.

The Theme

The Sonata as a compositional form comes from an initial thematic idea, that is, a subject that is presented at the beginning of the composition and that becomes the subject of a series of elaborations. The theme is that compositional element of the Sonata that is used as the starting point of a series of elaborations. We are all particularly accustomed to the function represented by this element: you will probably have also created a written theme, among the school desks, choosing an argumentative thesis around which to build and elaborate a development and a conclusion. You will surely remember that in the course the initial theme, that is, the topic of the writing, was taken up and revisited several times, the characteristic features were framed, or a particular part of it was highlighted, as when on the stage of a theater the spotlight illuminates an actor in one way rather than another. The medium of thematic processing is very powerful, you can use it to show sides of the starting subject of which it is difficult, listening to the theme as it is, you can notice a superficial listening. See how the actress's face changes in this fragment of Schumann's Manfred, interpreted and reworked in an unconventional form of Oratorio by Carmelo Bene. In the first seconds we see an almost deadly image, in this translucent black and white: the grazing light seems to emaciate the face, dehull it, the shadows project some disturbing black spots, which make some areas of the face disappear in the darkness of the background. But suddenly the light changes, and gradually the deadly shadows give way to a disconcerting light, as if those parts of the actress's face that were not visible before return from the underworld for a moment that seems eternal. The parts in light give way to shadows, and the face disappears completely in an oblivion black, as if the nature of the resurrection was actually inherent in the initial oblivion of the black hue.

This is an example of the creative power of thematic processing in Scenography: the actress can be considered the theme, the lights and shadows elements of variation. The same happens in Music: do not think of the Sonata Form as if it were a sterile compositional game between musical themes, because as you see the compositional technique participates in wider nuclei of meaning that we can find in everyday life, even in the theater.

Theme VS Subject: Synonyms?

The Subject is generally a simpler element of the Theme, we have already recognized it in the article on the Motet. A Subject we do not call It Theme because it represents only a melodic aspect, it is a solely horizontal motif and therefore does not provide for the complexity of several voices, more parts, counterpoints or harmonic overlaps.

Theme VS Motif

Motif is generally a small melodic element that has its own defined characterization while maintaining a simple structure, not intended for development. For this reason, unlike the theme, it could represent an isolated phenomenon in the composition.

Main Theme VS Secondary Theme

Just as on the stage we can find one or more actors, so in the Sonata Form we can find real thematic groups, which in most cases include two themes, main and secondary theme, often in this precise relationship:

| Main Theme | Secondary Theme | Example |

| In a greater way | Alla Dominante | FAM > DOM |

| To a lesser extent | To its major | SOLm > SibM |

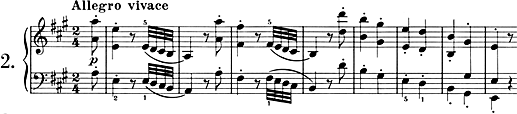

From this table we can deduce that the relationship between the two themes, main and secondary, is not a generic relationship of character: the strong relationship between the two themes is precisely harmonious. Often the secondary theme is even the same as the main theme except to be in the dominant or relative major shade. It is therefore not said that the two themes must be different from an extra-harmonic point of view. Take the Sonata Op. 2 Number 2 by Ludwig Van Beethoven: you can listen to an example below and order the paper score from the banner below. If you do, a small portion of your purchase will go to support this blog.

Through the criteria of equality, similarity and difference applied to the entire piece, we isolate the first eight bars in the example below.

Applying these three criteria means observing the general structure of the entire movement we are analyzing (in our case, the first), and distinguishing one or more components that undergo subsequent repetitions, processing, or that have differences with other components that follow the same behavior. To do this we usually use the rules of musical rhetoric that you find summarized in the public handouts of Maestro Stefano Pantaleoni, which you can find here. Let's briefly recap what was said earlier: analyzing the piece according to the criteria summarized in Stefano Pantaleoni's handouts and applying the principles of equality, difference and similarity, we have identified the repetitions of the compositional material in the piece, and consequently isolated the main theme.

Transition And Secondary Theme

Between the main theme and the secondary theme there is a very important transition phase, in which the first harmony is passed into the background so that the new one can emerge. This element further helps us to distinguish one theme from another. The transition imposes greater momentum and rhythmic continuity at the moment, weakens the compact form of the main theme by liquidating the melodic material to clean the scene in view of the entry of the subordinate theme. The function of the transition is to turn off the spotlight on the first theme and turn them on the second. Once the secondary theme is reached, the tonality of the secondary theme must be confirmed by an essential exhibition cadence, which closes the new shade. In the passage below, at bar 54 and following, we find the seventh of sensitive thought in the new tonality of E minor (Beethoven plays very often on the surprise effect, we in fact by tradition we would have expected an E major)…

… which resolves towards the second theme.

The Macrostructure

The compositional form of the Sonata lives the legacy of the ancient Suite, which we will talk about in a future article, so it is divided into several Movements. These Movements have very precise and recurrent characteristics. Usually there are three (but they can also be in different numbers, depending on the instrumental staff and the historical period):

| Cheerful | Charles Rosen describes the indications of the course of a Sonata not only as a suggestion for the speed that the piece must have, but as a term that refers at the historiographical level to a certain compositional form in the thematic elaboration. |

| Andante, Largo, Minuet. | A slow and decisive bottom movement. The use of the minuet is extremely rare. |

| Minuet, Allegro, Scherzo, Presto, Rondò. | The choice of the minuet is more frequent in the first period of the eighteenth-century sonata, think for example of the first three sonatas of Haydn; subsequently, as happens in Beethoven's sonatas, it fell into disuse. The movement that closes the sonata is sometimes called simply the finale, maintaining the trend relative to the allegro, the presto or the rondò. |

Internally, the sections of the various movements are often clearly distinguishable. We have described the literary theme as an initial organism destined for elaboration: in Music the process of thematic elaboration can take the name of Development. For example, in the first movement, at the beginning of the composition, you find an exposition generally included between two signs of repetition, followed by a development of the thematic material exposed and a resumption that re-presents the structure of the exhibition. Look at the scheme below:

Within these macrosections, which are the largest categorizations that we can do about the structure of a sonata, we find smaller elements, in particular in the exposition there is the main theme (P) followed by the transition (TR) and the secondary theme (S) , which ends in a closure (C). These acronyms are written in the same way also in the Anglo-Saxon analysis. The development does nothing but elaborate and vary the compositional material presented in the exhibition (main and secondary theme), which often remains easily recognizable. All this prepares the shot that generally has the exact same structure of the exhibition, with the only difference that the secondary theme is in some cases presented in the same shade as the main one: this feature makes the term modulating bridge that is sometimes used in Italian teaching place of the equivalent from the Anglo-Saxon transition confusing, and that is why we preferred not to adopt it. In explicit terms, without pleonastic repetitions, we can apply what has been said to the previous scheme obtaining the following structure:

In both the exposition and the resumption the conclusion coincides in most part with what is called codetta, although the composer could add an additional section at the end of the composition (after the conclusion of the shot) called coda. Here too we preferred not to use the Italian nomenclature so as not to create confusion between the two terms codette and coda.

The Cadences

In addition to what has been said so far on the macrostructural aspect of a Sonata, we can add in general that usually the entry of the secondary theme is announced by an intermediate cadence. This cadence is indicated by the abbreviation (MC). Each cadence that identifies rhetorical-compositional elements of the piece, and circumscribes them, takes a precise name in the analytical literature. Below are summarized the most important acronyms for the analysis of a Sonata (compare them with the diagram above):

| (MC) | It is generally found in the exposition, at the end of the transition which in turn follows the exposition of the main theme. |

| (EEC) | It is located between the secondary theme and the closing of the exhibition. |

| (ESC) | It is located between the secondary theme that we find in the resumption and the conclusion of the piece. |

Let's delve into these concepts in order:

(1) Both exposure and recovery may contain one (MC). The concept of median caesura (MC) introduced by James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy refers to a common phenomenon in the sonatas of the late eighteenth century, in particular those of Mozart, which consists of an intermediate exhibition pause (caesura) between the end of the transition and the beginning of the secondary theme. In practice, this compositional element is also found in sonatas before and after the eighteenth century, albeit with less frequency. The compositional phases of a (MC) are effectively summarized by Mark Richards in three points:

| Harmonic Preparation | It occurs at the end of the transition, and is usually represented by an (HC), or a Half Cadence, imperfect cadence. |

| Gap Della Texture | Between the end of the transition and the beginning of the secondary theme (S) there are pauses or a fill entry. |

| Acceptance of (S) | If the composition is about to begin with the new section (S), it will confirm the medial break that has occurred |

(2) The concepts of Essential Expositional Closure (EEC) and Essential Structural Closure (ESC) in the Sonata Form were introduced by James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy in the work Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata, and refer in most cases to the first satisfactory Perfect Authentic Cadence in (S) that passes to the non-(S) material. Since we have found the secondary theme (S) also in the Recovery, we have two different nomenclatures depending on whether we are in the first or in the second case: in the exposition we talk about (EEC) and in the recapitulation we talk about (ESC). In both situations, this moment determines the end of the secondary theme and therefore the beginning of the closure (C). You can order the manual from which this information was taken in the banner below: if you do, a small percentage of your purchase will go to support this blog.

The Phrase

Beyond its microstructural context (which we have seen in the notes of Master Pantaleoni), there are thousands of definitions of what a sentence is in the macrostructural field, many of which represent peremptory statements that refuse to be more precise than they are. In fact, it is very difficult to establish what a musical phrase really is, because it is not enough to dwell on its metric or rhetorical definition: who knows that you may not be the first to finally tell all the musicians in the world what a phrase in its substance is! For the moment, we must limit ourselves to its most recurrent formal characteristic, from which to move for a more in-depth research on the various exceptions with which it presents itself:

| Phrase | The phrase is a rhetorical element of four measures, having a complete meaning that can be related to other phrases of the same composition. |

| Sentence | The sentence is generally a fragment of eight measures containing two phrases of four measures. The first of these is called a presentation phrase, generally without cadence, and the second is the continuation sentence that ends on a cadence. |

| Period | The period is generally eight measures and contains two phrases of four measures, called antecedent and consequential. The preceding phrase consists of a basic idea that recurs at the beginning of the resulting phrase. Unlike the sentence, the period contains two cadences, a weak one to end the previous sentence and a strong one to end the resulting sentence . |

Let us now try as promised to focus on the particular characteristics that these rhetorical concepts go to assume within the Sonata Form, since in this precise compositional context Sentence and Period can be the rhetorical structures assumed by the Theme.

The Sentence in the Sonata

The Sentence that we find in this form is usually based on four characteristics:

| Basic idea | Arnold Schönberg will define it as a peremptory idea that is immediately re-proposed. |

| Repetition of the basic idea | The basic idea undergoes variations (very often of a harmonic type). |

| Fragmentation | You take only one particle of the basic idea and repeat only that. |

| Cadence Phase | The Sentence ends with a lock of almost always harmonic nature (Perfect Cadence, Suspended Cadence…) |

The Period in the Sonata

Since as we have said the Sonata is based on a theme, it is essential that you know how to distinguish the two types of rhetoric through which it can present itself. The other theme model is the aforementioned Period, the classic symmetrical model formed by two parts that must coincide and unite in a perfectly balanced way. It is the balance of two parts that complement each other: antecedent and consequential. A Theme that uses the Sentence compared to one that uses the Period has a much more dynamic forward projection: it is like something that remains suspended waiting to be launched. With Period you get a much more static and rested effect. The Sentence , on the contrary, starts with an extreme preposition that throws itself headlong into the argumentative material.

Forma-Sonata VS Forma Sonata

With the phrase Forma Sonata we have described a set of three or four movements, depending on the historical period and the instrumental formation, but sometimes we can refer exclusively to the first movement using the phrase forma-sonata. This concept, which may seem confusing, is actually quite simple: the form of the first sonata movement (sonata-form) follows the entire compositional behavior of the Sonata Form, because it presents a structure that replicates in small the macrostructural meaning of the composition. In Italy we refer to the sonata-form also with the term Form of the First Movement. In the first Movement of a Sonata, therefore, not only a thematic microstructure is exposed, but also, on a reduced scale, a macrostructure that anticipates the compositional aspect of the entire composition. To this we must add that in most cases of a sonata form only the first movement is in sonata-form, while the other two do not follow in most cases the sonata-form, presenting themselves for example in the aspect of the minuet, notoriously quadrithematic. An example is the second movement of the Moonlight Sonata Opus 27 Number 2, with the trio and all the typical configurations of the minuet. I played it for you in the example below:

You can buy the paper score of this sonata from the link below. If you order it through the banner below, a small percentage of your purchase will go to support this blog.

Conclusions

The Sonata Form is certainly among the elements of Compositional Analysis that you must know more accurately, because it has represented, from its birth to the present day, an essential compositional form (together with that of the Fugue). Mastering the sonata means knowing how to read and interpret more fluently most of the scores that you will find in front of you. If you're looking for more insights, you can turn on blog notifications or subscribe to our YouTube channel. See you in the next article!

- History Of The Piano – The Fortepiano - July 12, 2022

- Curt Sachs – History Of Organology At a Glance - July 8, 2022

- Giuseppe Verdi – Rigoletto, Il Trovatore, La Traviata - June 29, 2022