Introduction

In this article I will try to explain to you, in the most practical way possible, my very personal method of study for piano scales. I'll pretend you don't know anything about this topic, and I'll guide you step by step in the study: you can use the index above to easily navigate through the contents, to skip the ones you think you already know or to reach those in which you do not feel very prepared. If you follow me in this article, you will discover that this seemingly insurmountable mountain of piano stairs is actually approachable starting from a precise organization, inherent in Music.

Practical Definition

Many manuals, blogs, sites, video tutorials begin to talk to you about piano scales giving you a theoretical definition. So, to avoid repeating ourselves in definitions that you can find practically everywhere online, we should jump directly to the practical definitions of Piano Reading Method:

A scale is a succession of melodic intervals by joint degree, regulated on a practical level by a particular type of fingering, that is, precise indications on which finger should lower a given key.

Piano Reading Method, p. 249

Fingering

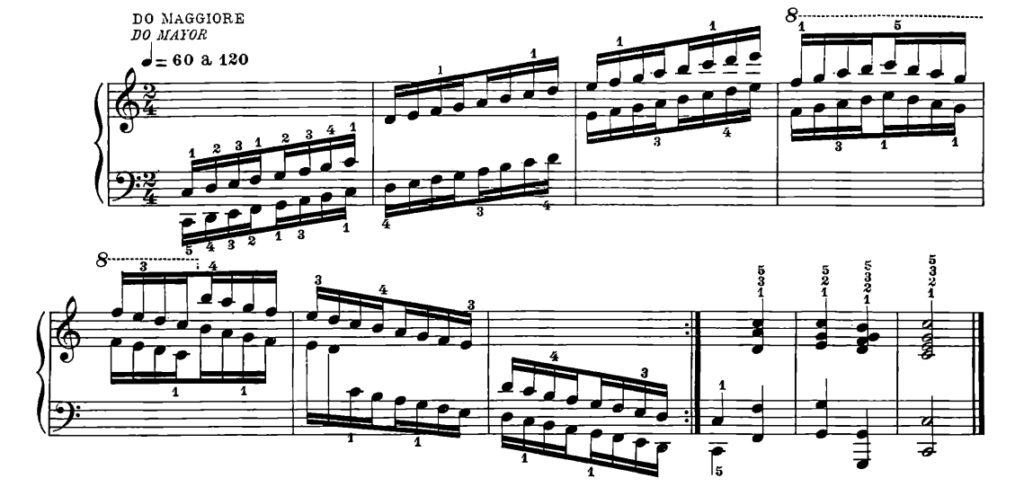

Look at the example below. When you read the scales on the piano, the numbers that tell you which finger should lower a certain key (fingering), are shown above or below the notes in the score.

Fingering numbers refer to the orderly progression of the fingers, starting with the thumb.

| 1 | Thumb |

| 2 | index finger |

| 3 | Average |

| 4 | Ring finger |

| 5 | Little finger |

The numbering applies in the same way to both hands. For example, the fourth finger of the hand, indicated with 4, will be the ring finger both in the case of fingering for the left hand and that of the right hand.

What Scores To Play Stairs At The Piano?

An excellent text for the study of scales is the manual The virtuoso pianist by the composer French Charles-Louis Hanon, which shows the scales on the piano in all tones and on four octaves, as required by the first conservatory exams. If you do not have this text, I strongly advise you to get it as soon as possible: below you will find a banner to receive it in the day. Almost all the greatest pianists in the world started from this score. If you buy it from the link below, a small part of your purchase will go to support this blog. I recommend, among other things, this precise version since the additions of A. Schotte will give you a great help in the later stages of the study.

Why Do I Have to Study Stairs At The Piano?

The answer will surprise you: once you master the scales on the piano, you can use them to read and play any succession of melodic intervals by joint degree: after such a consideration, I hope you will give the scales the utmost importance.

Reading scales and speed

The scales represent an essential tool for reading most of the piano repertoire. Mastering it is also fundamental for the study of fingering, since they can be the model of many fingerings of melodic successions: we have in fact seen that the joint degrees can be fingered following the fingerings of the scales. In other words, if you have to choose which fingers should lower the keys in any melody by joint degree, you can consider as a general rule to always start from the reference of the fingering used for the scales: from there you can build the necessary exceptions, depending on the context.

Phase 1: PFM

The concept of Fundamental Position Of The Hand (PFM) is very simple: its effectiveness in the study of piano scales will leave you amazed. I have prepared a video to avoid reading rivers of words that for practical reasons are often quite ineffective. In the video I will introduce you a little to the whole discourse on the study of stairs with some practical examples, so do not read further if you have not seen it before or you risk not understanding anything. Click on the play button below, see you there!

Translating into textual terms what you have already seen in the video, once you have clarified the elements of the scales you have to reduce into "segments" the four octaves of each scale on the piano, starting from the movement that the hand must make in two fundamental positions of the hand (PFM) to pass the thumb or to pass over the thumb, in order to make a change of perspective in your way of conceiving stairs: moving from a horizontal to a vertical vision. The segmentation, from a harmonic point of view, is carried out through two clusters, clusters of adjacent notes as in the example below.

In some cases, to correctly implement the pfm decomposition, you will have to consider the first notes of the scale as arrival notes, that is, as if you had already played an octave before arriving at them. As we have seen in the video above, the example of the B-flat major scale the fingering generally provides 2-1-2-3 for the right hand: in this case the 2 (on B flat) will not be taken into account, since playing the first cluster including the B flat would mean changing the fingering provided for the scale; the clusters assigned to the two fundamental positions of the hand will be composed respectively of C=1-re=2-mi(flat)=3 and f=1-sol=2-la=3-si(flat)=4.

Practical advice

The moment you apply to the piano scales the technique that I showed you in the video above, you will have to try to understand if indeed all the fingers are lowering the keys to the end, if your hand is relatively relaxed. If you're lowering all the keys but you're stretched out as if you're lifting a four-ton elephant, you're doing something wrong: try to pinpoint unnecessary tension points, and leave most of the work to the weight of your hand and arm. Do not forget that to lower a key you need a very small force: if you are trying too hard for this purpose, something is wrong.

Step 2: Preparation

As you may have guessed from the video above, the fundamental position of the hand will not necessarily involve the simultaneous use of all the fingers. As you can see in almost all the examples of piano scales that I make you in the video there are fingers that are not lowering any key. For this and many other reasons, the fundamental position of the hand must be prepared mentally and in advance of the moment you arrive on the keys related to it. It is absolutely counterproductive to prepare the hand when the fingers reach the keys, making only then the necessary adjustments to position you correctly and on the right keys.

Step 3: Imagination

An effective exercise to anticipate in the mind the various fundamental positions that the hand will have to assume when you study the scales at the piano is to think of two fundamental positions of the hand in the form of notes written on the pentagram. In other words, you will have to imagine the score without reading it: try to imagine a set of written notes and then play them. When in the future you have to read a scale on the score, this training will allow you to open your hand in advance, before touching the keyboard, in correspondence of the keys you imagined in the form of notes. In this exercise you will have to maintain a high level of attention both during the opening of the fingers and during their closure. For example, in a C major scale you will have to mentally anticipate the arrangement of the hand on the four-key white series while you are still on the three-key series, thinking about how your hand will have to fall on them before it reaches them.

Step 4: Slow VS Slow Motion Study

Many bad teachers to introduce the student to the study of the stairs at the piano simply tell him to practice them slowly. Now this is a double mistake: on the one hand, because without giving a coherent system of study, as we are trying to make this article, the student can not understand what he should practice slowly! In other words, the very subject of this supposedly slow practice is missing; secondly, because practicing slowly is absolutely counterproductive: if anything, you should practice in slow motion. The two conceptions are very different: practicing slowly can mean not having an overall idea, an idea of how in the final stages of the study a certain piece or fragment of it that we are studying (in this case a scale) should play. Studying in slow motion instead means having a broader conception, but slowing down the process until it becomes controllable. Here on Piano Reading Method I will reiterate several times to imagine that you are playing in slow motion during the study (and not slowly).

Step 5: Theory VS Practice

The practical schematization of theoretical-discursive acquisitions is fundamental during the practice of piano scales. I will therefore take for granted all the theoretical notions we have talked about in previous articles. This does not mean, of course, that theory is useless: on the contrary, this is the raw material of our practice, but we must translate it into terms applicable to executive practices. Here's how:

(1) In the article on the circle of fifths we said that for each shade you do not have to keep in mind more than three alterations for each key armor. The same principle also applies to the notes that, with respect to the major scale, must be remembered in order to build the relative harmonic and melodic ascending or descending minors; in fact, there are also three of these notes, and they proceed by joint degree: sixth, seventh and first degree of the scale. It is therefore advisable to conceive them immediately in descending order (for example: la-sol-fa) by placing from time to time the necessary accidents (diesis or bequadri), without keeping in mind all the notes of the minor scale. In general, all minor stairs must be considered in relation to major stairs, since their key armature is the same;

(2) The harmonic minor scale has the seventh degree altered to give rise to the sensitive both in ascending and descending, because as we said in the previous article on intervals melodic intervals are always considered starting from the most serious note, regardless of their ascending or descending direction. The ascending melodic minor scale has altered seventh and sixth degrees, to give rise to the sixth major, while it has a bequadro respectively on the sixth and seventh degree in the descending phase, or, if you are not coming from an ascending melodic scale, no new accident with respect to the key armor of the relative major scale, to give rise accordingly to the necessary minor and subtonic sixth;

(3) At this point, it is necessary to memorize and repeat in mind, imagining the score and not the keyboard, which notes are actually altered so as not to mentally consider the keys that are not part of the scale. It will be difficult to get confused if you follow the above suggestions, but it is good not to forget that, to give an example among all, the sol diesis associated with a precise key in the scale of A minor harmonica should not be confused with an A flat.

Phase 6: Circle of Fifths

Since each minor scale is to be considered in relation to its relative major, it is essential to know perfectly the complex of key armatures: to do this, a practical schematization of the circle of fifths is necessary. We at Piano Reading Method are convinced that we must know, from a practical and not only theoretical point of view, what common characteristics have the two directions respectively clockwise and counterclockwise of the circle of fifths:

(1) Clockwise it is obtained that the accidents in key (starting from the fa towards the mi) start from two white keys that are replaced by two black keys (following the order: the natural F that is replaced by the black key makes diesis, and the natural C that is replaced by the black key do diesis); the last alterations are encountered respectively on two white keys that are replaced by as many white keys (on the natural mi, which is replaced by the white mi diesis key, and on the natural si, which is replaced by the white si diesis key). It will therefore be necessary to consider first of all the left portion of the white keys on the two distinct series of two and three black keys. In the following examples, the first and the last two notes altered by the key armature that is obtained by proceeding clockwise on the circle of the fifths have been respectively highlighted and the last two notes have been crossed out.

(2) Counterclockwise instead, it is obtained that the accidents in key armor (starting from the si towards the C) start from two white keys that are replaced by two black keys, (in order: the natural B, which is replaced by the black B flat key, and the natural E, which is replaced by the black E flat key); the last alterations are encountered respectively on two white keys that are replaced by as many white keys (on the C, which is replaced by the white button C flat, and on the F, which is replaced by the white button B flat). It will therefore be necessary to consider first of all the right portion of the white keys on the two distinct series of two and three black keys.

From these two examples it is easy to see how the fulcrum of the key armor always starts from the right or left ends of the series from three black keys.

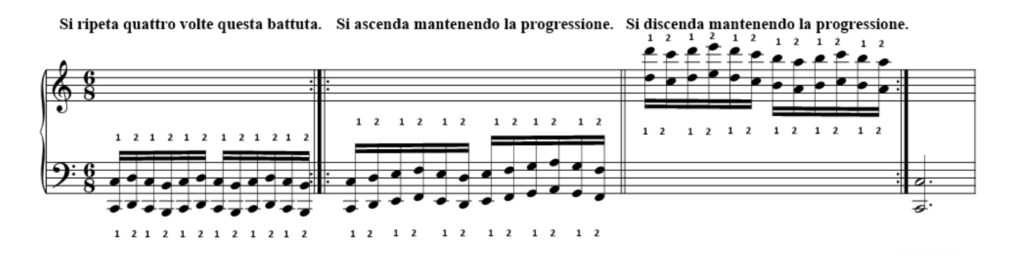

Step 7: The PDP

With the concept of fundamental hand position, studies on the five fingers take on a seemingly new importance. In particular, during the study of the stairs particular attention must be paid to the passage of the thumb, that is, to what in the piano scales represents the study of the correlation between two fundamental positions of the hand. In other words, a little less complex, it is essential that the hand moves sideways from left to right, or from right to left, slightly pulling the wrist towards itself, so as to prepare the thumb on the key to be played with the same, in the most efficient way possible. This movement of the wrist should be practiced by mentally dwelling on the finger that plays before the thumb and at the same time preparing the latter on the key that will have to play. The following exercises, which I have transcribed in summary form from the manual that I have shown you above, are particularly effective for the study of the passage of the thumb under the second, third, fourth or fifth finger:

Exercise 1 – Second Finger

Exercise 2 – Third Finger

Exercise 3 – Fourth Finger

Exercise 4 – Fifth Finger

Step 8: Reduce the margin of error

When studying the stairs you will have to keep in mind that the black keys leave a margin of error on the finger, sometimes moved to the right, sometimes to the left, by virtue of their arrangement. This provides, playing in an ascending or descending direction, a variable distance from the center of the black key to that of the adjacent white key. From a practical point of view we could translate what we have said so far as follows: with respect to the center of the groups of two and three black keys, these are arranged in a "fan"; the black keys arranged externally with respect to this ideal center give a variable margin of error depending on their location.

In other words, the black key to the left of this ideal center will always have a greater surface area to the left than the center of the white key that precedes or follows it; on the contrary, the key located to the right of this ideal center will have a greater surface area to the right. In the case of the series of two black keys, it can be said that the ideal center of this "fan" coincides with a point of the imaginary axis that divides the white re button into two longitudinally. The summary diagram is proposed below (par. 4 – Chap. I), so that it is integrated with the latter considerations of a practical nature (Fig. 110):

Conclusions

That's all for this article, don't forget that you can request your own tailor-made individual private lesson by simply clicking here. I will personally follow you in all your difficulties, we will achieve your musical goals and, if you need it, we will further deepen the discussion on the stairs. See you in class!

- History Of The Piano – The Fortepiano - July 12, 2022

- Curt Sachs – History Of Organology At a Glance - July 8, 2022

- Giuseppe Verdi – Rigoletto, Il Trovatore, La Traviata - June 29, 2022