Introduction

In this article I would like to talk to you in the most practical and concise way possible about Franz Liszt’s attempt to get out of the field of tonality: he arrived at sounds that were in fact new and unusual for the compositional panorama of his time. The consequences of this attempt will be reflected in a whole series of musical considerations that we will have the opportunity to deal with later in a practical way, analyzing in depth some scores. Many of the works of the mature Franz Liszt are studded with the attempt to get out of the tonal system. When we talk about the mature Franz Liszt we identify a very specific phase of his life (from 37 years of age onwards): given that on the biography of this composer there is a morass of offline and online information, often impractical, I suggest you take a look at the summary that we have dedicated to him here before proceeding to read this article.

The Bagatelle Sans Tonalité

In one composition in particular, called not by chance Bagatelle Sans Tonalité, the intent to get out of the tonal sphere becomes the compositional fulcrum of the entire piece. This Bagatelle is also known by the title of Mephisto Walzer IV: we are talking about the latest Franz Liszt, now one year after his death.

As you can see from listening, finding the tonality of a piece written by the mature Franz Liszt is among the most difficult tasks that can be assigned to a pianist. The composition employs all the stratagems then known to avoid affirming the tonality, from the harmonic progressions without a point of affirmation, to its well-known colors. In the next few lines we will try to analyze the works of the Hungarian composer to understand if a piece without a tonal statement can really stand, what its meaning is and in what sense there is no point of clarification of the tonality.

Compositions In Comparison

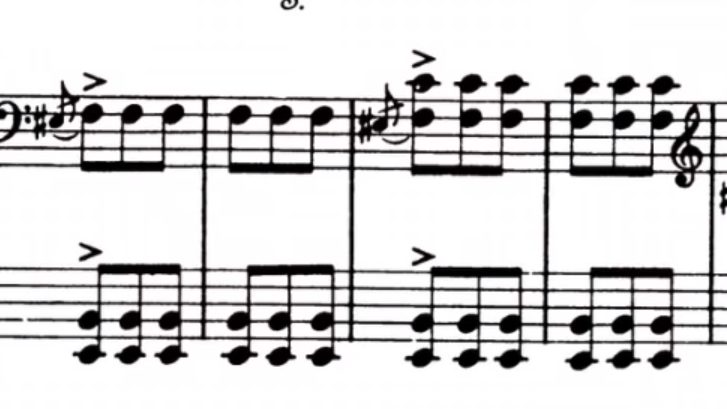

In the mature Franz Liszt we see a complete reversal of the compositions of the youth period, towards an experimental approach that anticipates in many ways the discoveries of the twentieth century. For example, in Mephisto’s first Waltz, originally conceived for orchestra and then transcribed for piano, we find the overlapping of fifths, a widespread procedure among twentieth-century composers. Look at the example below:

I leave you to listen to the two versions of the opera, the orchestral and the piano. Below, you will find what in my opinion is the best edition of the piano score of the original work: if you order it from the banner below, a small part of your purchase will go to support this blog.

There is a piano reworking of this piece by Ferruccio Busoni, in turn reworked by Vladimir Horowitz, a version that I submit to your attention to allow you to easily grasp the dynamic aspects of the original composition:

In Ossa Arida, another of his mature compositions, we find the overlapping of thirds without particular tonal intent:

The same happens for the fourth in the third Waltz Di Mefisto:

In the last agreement of Nuvole Grigie (Nuages Gris), we find a harmonic procedure that we could define impressionistic: just as for the impressionist painter it was not important to adhere to the academic, formal model of painting – where every bust, every drapery had well-defined traits and forms – so in Franz Liszt we witness the encroachment from the dotted margins of the tonality.

Some interpret it as an eleventh chord. But it is easy to understand that this is absolutely not the case, because this is structured differently. In fact, although it is theoretically possible to reorder the agreement above as follows …

| THE |

| AGO ♯ |

| YES ♮ |

| SOL |

| ME ♭ |

… however, marginal contradictions remain, such as the strangeness in the omission of the seventh, which is not usual in the writing of the eleventh chord, and deeper contradictions that could be highlighted about the traditional use of a similar agreement:

| Name | Acronym | Structure |

| Eleventh Di Dominante | Sun11 | Do–Mi–Sol–Si♭–Re–Fa |

| Eleventh Minor | Sun11 | Do–Mi♭–Sol–Si♭–Re–Fa |

| Eleventh Major | DoM11 | Do–Mi–Sol–Si–Re–Fa |

| Eleventh Dominant Surplus | Sun9♯11 | Do–Mi–Sol–Si♭–Re–Fa♯ |

| Eleventh Major Surplus | DoM9♯11 | Do–Mi–Sol–Si–Re–Fa♯ |

As you can see, in none of the traditional forms of writing an eleventh we find as a constitutive triad the excess triad used by Franz Liszt: the eleventh in fact is formed starting from a major triad, you will never find do-mi-sol♯ or, to give the example proposed by Franz Liszt, mi-sol-si♭♮.

The Difficulties Of Analysis

Before going further we must make an even broader and more general consideration: trying to define a chord in the manner of Classical Harmony, we are aiming to give it a very precise meaning, that is, we are trying to understand what its role is within the composition to draw up an overall musical analysis of the latter. We could call the supposed eleventh that we have examined above as a polychord, following a definition of classical harmony. Or we could say that it is a variation for thirds of the Hungarian scale, which perhaps would be more apt. But here the form is used in such an original way that it does not have great evidence in the previous literature. Therefore the question arises whether it is useful to analyze an agreement according to the criteria of Classical Harmony, given that this matter seems to serve us only to label it as an agreement of which there are no significant examples in the previous literature.

Classical Harmony And Atonality

The problem does not lie in Classical Harmony, but in our mistake: we impose on it a task that it cannot fulfill on its own. If we demanded that it tell us by itself what the meaning of a composition is, we would find ourselves saying: “I must possess data that indicates to me that a certain succession, a certain chord, a certain cadence, has been used mostly in a certain way to mean mostly a certain thing … This is the only way to understand how to interpret the meaning of this choice of Franz Liszt!” But as with all relatively new phenomena, with the final agreement of Franz Liszt’s Grey Clouds we would be in great difficulty. And we would blame a matter that has no guilt, because it has never placed itself as a universal pivot of interpretation of musical meaning.

Why Did Franz Liszt Felt The Need Of The Atonal World?

And yet, even if traditional harmony has never been the fulcrum of the indisputable interpretation of the absolute meaning of a piece, for some to do the analysis of a composition still means to limit themselves to a traditional harmonic analysis: we at MDLP, following the most recent line of thought of the great theorists of the twentieth century (Erickson, Dahlhaus, etc.) we consider the analysis in a broader sense by relating sound, harmony, melody, rhythm and growth process of what we are examining. Defining each of these elements individually is not enough: it is necessary to relate them to each other. So let’s go back to looking at Franz Liszt’s chord, focusing on the features you read in our previous article on Sound, which if you missed yourself you can find here. Let’s do it to understand why Franz Liszt would have chosen to trespass from the world of tonality, and what it means on a musicological level.

You will surely have noticed that watching these last bars starting from the magnifying glass of the sound is much more significant, it returns a more relevant analytical experience. This treatment of sound, in fact, at the end of a piece, is a process widely used by composers such as Claude Debussy. In the example of Franz Liszt above, harmony enters the game of sound by increasing the feeling of suspension, with that fa diesis that does not resolve until the penultimate beat, keeping the rest of the harmony unchanged, which continues below like a carpet. That ray of light given by the sol, which represents a safe resolution within an apparent loss of any tonal horizon, plays on an effect that has little to do with the traditional rule of resolution. In fact, he uses the rules of Harmony in a metaphorical sense, trying to give extramusical meaning to the compositional content. About this poetic ideal of Franz Liszt, common to many romantic composers we talked about in the article on Romanticism, which you can find here. The fact that Harmony is not treated literally does not imply that it is in an unreal or imaginative way: the metaphor is in fact a rhetorical process, which reveals figurative perspectives of a given phenomenon. When we read in the dictionary that a word has a literal and figurative meaning, we do not think that the figurative meaning is false: for example, if someone came to us and told us “You are really a beautiful donkey!” we probably wouldn’t answer him, “What do you say, don’t you see that I don’t have a tail?” but we would continue the discussion differently, attributing to his consideration the figurative meaning of stubbornness. The same happens in the agreement of the Grey Clouds: we refer to a true, authentic meaning, using terminologies that recall the figurative perspective.

Atonality Or Omnitonality?

Although there is no precise confirmation of the tonality, classical harmony can still explain what happens in Gray Clouds from a tonal point of view. We have identified a precise structure taken from the Hungarian scale, which could also be read as a polychord. We have also said that the analysis must always proceed taking into consideration the Classical Harmony as a material to be enriched and integrated through the relationship of sound, melody, rhythm and growth process. At this point it is natural to wonder if Franz Liszt’s is really an atonal approach, and if it is not rather an omnitonal approach (from omni, “all”): in fact, the structural processes of tonality are used and exploited, but the tonality remains open. The same feeling of a shade that is not affirmed is part of the tonal process, because it works by assuming a tonality (albeit absent). In truth, that of omnitonality is a definition espoused by Liszt himself, who wanted to indicate a music that starts from the assumptions of Classical Harmony, which are those of tonality, but floats on it; that the piece contemplates one, two, ten tones is indifferent: it will not assert itself on any and will limit itself to using only the assumptions, transforming them into a significant poetic-musical aspect.

Conclusions

We could conclude by asking ourselves if the poetics of Franz Liszt, in this new meaning that we have explored, is to be interpreted as a prelude to the twentieth-century approach to tonality, which has very often dealt with expanding, distorting and denying it. But for today’s article we stop here: continue to follow us, in a next page we will continue this very interesting speech. See you in tomorrow’s article!

- History Of The Piano – The Fortepiano - July 12, 2022

- Curt Sachs – History Of Organology At a Glance - July 8, 2022

- Giuseppe Verdi – Rigoletto, Il Trovatore, La Traviata - June 29, 2022