Table of Contents

Introduction

Very often those who listen to Music do not wonder why a composition is written in a certain way: the compositional phenomenon is considered popularly the product of mostly irrational decisions, which are not always translatable into words. When we answer this question in such a simplistic way, the process by which composers implement their artistic choices is not made explicit. This is absolutely detrimental especially for performers, who have the task of illuminating the most relevant characteristics of a composition, and therefore need a critical and analytical knowledge to ask the right questions about the score. Why does Clementi write the first bar of Sonatina in C major opus 36 as do-mi-do-sol-sol and not sol-si-sol-re-re, which would be the exact same thing but transposed? Why is this feature relevant? Why doesn’t he write in nine eighths instead of four quarters? Why doesn’t he use wider ranges? Why is each highlight followed in the theme and theme repetition by a waterfall and a geyser of notes respectively? Why are those notes rhythmically worth half of the larger figure we find in the first bar of the theme? All these questions are very complex, but they start from a premise that is very clear: they do not ask, in a general sense, why is the composition written as it is written?, but more precisely why is that composition written as it is written and not in another way?

I anticipate that the answer will be contained in the whole process that I will show you between these lines, since it cannot be summarized in a single sentence. We will use a method that I have personally devised, in which we will give free rein to our compositional flair and then gradually realign ourselves with the composer’s intentions. If you are an expert in Composition, you will probably find many of the passages shown below cumbersome and superfluous: please, remember that they have a purely pedagogical purpose and are written specifically as a beginner would write them. I will assume that you have a basic knowledge of Solfeggio and Harmony, that you know how to analyze a simple piece according to the techniques indicated here. If you still can’t do any of this, don’t worry: you’re always in time to get started! Some articles of our blog will suggest the study techniques to proceed at a fast pace. Start from the article on Solfeggio that you find here.

Historical Premise

Before starting, a brief historical premise: the piano began to configure itself as we see it today only starting from the innovations of the Viennese manufacturers on mechanics. It is no coincidence that we speak of the “Vienna School” when we indicate those composers (Mozart, Beethoven and Haydn) who first gave impetus to the development of the impressive potential of this instrument. Much of the piano teaching was written in the period of the First Vienna School or in the years immediately following, and even today in the Conservatories texts of that period are used to teach the rudiments of music. We chose Muzio Clementi to take two fish with a single bait, and follow the purposes of this Blog on the Piano: deepening this author will allow you not only to have a historical knowledge of the roots of your instrument, but also to carry on with your studies if you want to deepen his repertoire for an academic exam or a private goal.

Step 1: Choose a template

If you look at the biographical information we have of the great composers of the past, you will find that they learned to write music by copying manuscripts or editions of the best known compositions many times; then, having reached a certain degree of knowledge, they reworked, transcribed and varied the scores they had collected. It was only marginally a requirement dictated by the fact that there was no press as we know it today: through rewriting, composers learned from their predecessors. Only at the end of a long training course could it happen that they were interested in unknown composers, once they had acquired the means to be able to search for a certain originality: many of the composers we know today were discovered and made famous in this way. Of course, the process of transcription of a score in itself is not enough to have the means to reason about the compositional phenomenon, so it was not uncommon for a composer to simultaneously make serious studies of theory and counterpoint, solfeggio and so on. That is why in this article we will give these matters for granted, at least in their rudiments. With these premises we try to follow the example of the greats who preceded us: below you will find the score of the aforementioned Sonatine by Muzio Clementi, in the URTEXT edition that I personally recommend. If you buy it from the banner below a small percentage will go to support this blog.

You may wonder why we chose some rattles to start this journey. The answer is simple: they follow the sonata in miniature, a form of which we have spoken extensively in the article you find here: if you remember, we had said that the sonata had been used by the most illustrious masters of the past as a pedagogical tool, since its structure was used in a miniaturized way to produce compositions in sonata-form (which were not necessarily real sonatas ). We had said, in other words, that even an Opera Overture can be in sonata-form. For this reason, the student, often at first sight, had entire collections of sonatas performed in order not only to prepare him to perform them, but also to shape his mindset. This is because the sonata contains in miniature many of the compositional stratagems that are used in the musical universe. The sonatina is nothing more than a simplification of the sonata, that is, a smaller sonata: perfect, in a word, for you who are on a blog dedicated to the Piano and you are taking your first steps in the world of Composition.

Step 2: Learn From The Model

Of Clementi’s collection of twelve sonatines we examine the first composition: we will use them to invent possible alternatives of writing, which we will compare with the compositional solutions adopted by him; we will then try, at a later time, to imitate them as much as possible by “correcting” our initial idea. Correcting is in quotation marks because all those that we will define “errors” of our initial invention, will actually be only the ways through which we will explore the composition we have in front of us: if we have to imitate a four-quarters in C major, as in the case of the first sonatina, it is clear that any choice we will take that is not to write in four quarters a piece in C major will result, sooner or later, approximate… But for the purposes of our exercise, this is just the ideal: it will allow us, as you will soon see, to explore and give free rein to our creativity and at the same time to compare our instinct with a possible compositional solution. Are you ready for the rich and unexpected discoveries we are about to make?

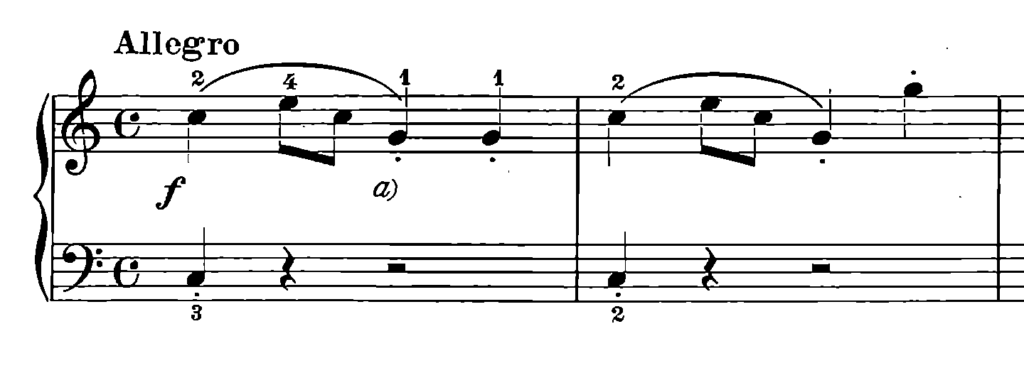

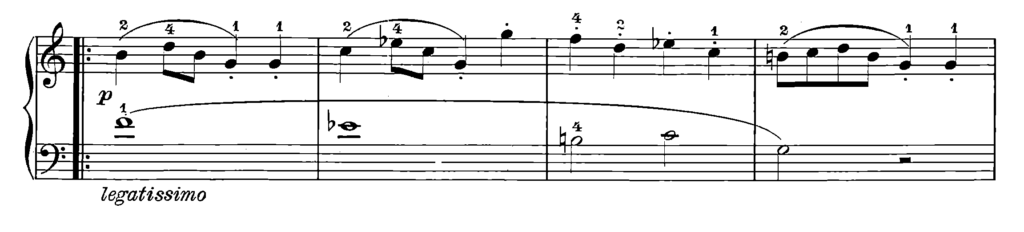

The first thing we have to deal with is to identify the main theme of the composition. Doing so is not easy, because this could be enclosed in an engraved as in a whole sentence. An effective method to understand which case we are talking about is to evaluate the repetition behavior of engravings and sentences. I’ll give you a practical example: let’s examine the first line and ask ourselves if this can already encompass the theme of the composition.

Seen in this way, it tells us everything and nothing. The C to the bass remains firm, the chord is that of C major. The melody ends on a sol. From this analysis the fragment would seem to have a complete character, but if we do not compare it with what comes next we cannot draw any conclusions. Let’s broaden our gaze towards the next joke:

The first fragment repeats itself and there is only a small variation on the last sol, which is played at the upper octave. But this in itself does not confirm whether it is already the subject or not. Let’s see why by further widening our gaze:

As you can see, the more we broaden our gaze, the more we become aware of new elements. The two opening bars are repeated almost identical to beat five and six, and there is a cascade of notes that separates the first repetition (bars 1-2) from the second (bars 5-6). Widening the gaze even more, we realize that that same cascade of notes is repeated further with some variation:

The first valid repetition to distinguish the theme is therefore that of the first four bars, because after the four bars we have a repetition of the elements already seen in varied form, and there is no modular repetition of the eight-bar scheme in the first section of the piece:

The latter is the only real first confirmation data for the identification of the main theme. But this fact alone is not enough: let’s look at the second section of the sonatina. It starts in a familiar way:

And it continues in an equally familiar way towards the G, as had happened for the first section of the song:

The scheme does not find repetitions of sections larger than this until the end of the composition: a fact that irrefutably confirms our initial intuition. Now that we know that the theme is composed of the first four bars, we can draw a first conclusion: Clementi chose to repeat it twice in the first section of the song. Beyond this, there are hundreds of other characteristics that we could notice, for example the use of an arpeggio for the first engraved, or the point where the transient alteration is introduced, but we must proceed one step at a time. If for now we can create a four-line theme and have it repeated twice, we can consider it our first mission accomplished.

Step 3: Follow The Theme

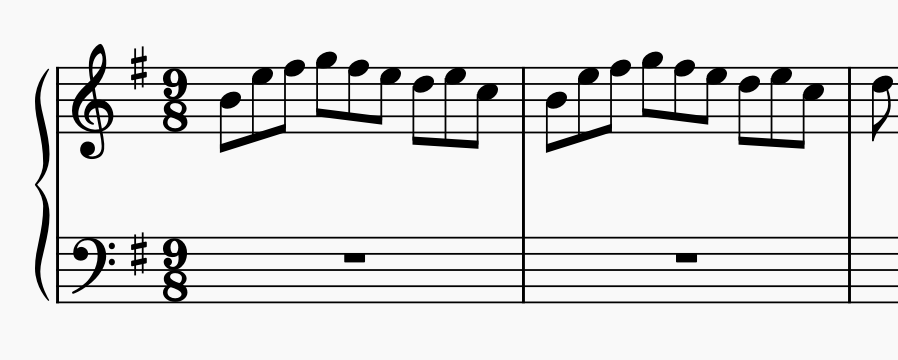

Given the previous considerations, we just have to devise our four-bar theme. We can choose the shade that Clementi used, or move elsewhere. The same applies to the indication of measurement: for the moment we must not take the tonality of the piece or its harmony as binding data, because they specify conceptual subcategories that are absolutely not decisive for the point of the exercise in which we find ourselves. For the moment we can move in a similar major tonality, such as G major, and in a completely different measure indication, such as nine octaves. The important thing is that the result satisfies us and responds to our first purpose, which for the moment is exclusively to create a four-bar theme that is repeated twice. Let’s start by defining the first melodic recording: Clementi gives us two examples, an arpeggiato inciso repeated for two bars and a melodically dense incisor, always repeated for two bars but with very close notes and sporadic jumps. We choose the one we like the most.

We used possibilities of a pattern with joint degrees and sporadic jumps. For the second segment of the theme, we use the arpeggiated form:

If you know Harmony, you will have already realized that at bar three and four nothing has been done but to add two arpeggios of D major to which notes have been removed. This solution is absolutely trivial, but we are now not interested in creating a masterpiece that will remain in the History of Music as much as anything else rewrite following the forms used by Clementi to reason about his compositional choices and draw some possible conclusions. Now we must find a way to repeat the theme by returning to the initial note: if we want to follow Clementi’s harmonic model, we must replace the yes that we had previously written with a sol: in this way we begin and end on the tonic, exactly as he did in C major. Here is the result:

We started with the realization of a melody, and now we have to choose an accompaniment. As you well know if you know Harmony, the process can be reversed: you can also start from a harmony bass, and in that case everything is simpler, and then make a melody. In this context the detail is superfluous: the important thing is not to lose sight of what are the chords and tonal support points that Clementi is using in his composition. The process must not be untied: you must not think in terms of harmonizing a melody or vice versa, you simply have to imitate the conception you see written. In fact, the theme is also made of a precise harmony, which cannot be disconnected from its melodic aspect. Let’s see how Clementi moved: on the bass in the first two bars we have a C, it is written detached and lasts only a time to give the character of melodic-rhythmic momentum to the right hand. In the next two bars, which represent the model we used for our first two bars, the C is repeated to balance the rhythmic momentum of the right hand and is followed by a series of notes that have the cadence function of connecting the theme to its repetition. We do not need the cascade of notes after the first two bars, because it is not there that in our composition the theme is repeated. Moreover, not having chosen to start with the momentum of the arpeggio, a firm note at the bottom flattens the already not particularly lively texture. In the second section, when the theme is repeated to the minor and therefore no longer has that initial momentum and freshness of when it was presented for the first time, the author remedies by creating an accompanying line that from the acute proceeds to the grave with wave motion: the end of the melody is on the lowest note touched by the accompaniment.

We give the same impetus desired by the composer by increasing the duration of the initial note and making it rest on his accompaniment, as happens in the original composition. We can take inspiration from the repetition of the theme to the minor and choose a line that is not flat, probably with this hybrid we will get a happy solution since we have not chosen to start with the arpeggio and the character of the descending momentum is not so strong in our composition.

Step 4: Analyze The Microstructure

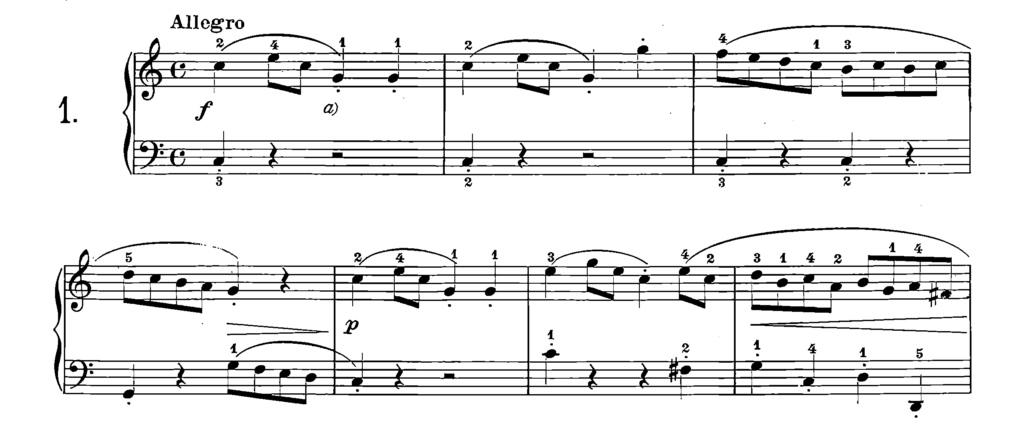

Now that the general structure of the repetition of the theme is basted, let’s dwell on some details. For example: what happens at the interval level? Clementi moves the theme and its repetition respectively within intervals of octave and ninth.

We hear how the two fragments sound if we keep them within this range.

The highlight of the melody in bars three and four is now assigned to a tempo that is not in beat.

Let’s see if Clementi does the same:

At first glance it would seem so, but if we look better we realize that our use is very different from that of Clementi. He uses the melodic culminations upwards and downwards to prepare the momentum on the beating of the following notes: first, upwards, he prepares a descending waterfall; then, downwards, it prepares a rapid ascent of introduction to the new tonality of G major. If our result seemed unsatisfactory because it was too far from Clementi’s, this is probably one of the reasons. Let’s apply what was discovered to the four bars of the theme:

The result is more similar to Clementi’s outcome than before, but if we look carefully we realize that in the sonatina in C major that we have analyzed he never touches the climax of the melody several times in the same theme:

In our composition, on the other hand, the highlights of the melody upwards and downwards are touched several times in the repetition of the theme, something that does not happen in Clementi. The reason for this trivial mistake is simple: if we have to take the largest rhythmic figure from the initial theme and then halve it to write the rapid ascending and descending scales that start from the culminating points of the melody, the high number of notes that we can make stand in a time allows us to tell the truth little creativity. We can identify the two mistakes that led us to this point: the first is that of not having chosen a theme with wide rhythmic figures, the second is that of having written the piece in a compound measure, which provides more notes for each beat than its relative simple measure.

Let’s think for a moment about how many considerations we have managed to make so far about Clementi’s composition: even if they were aimed at correcting our composition, they told us something more about why the composer decided to write in four quarters rather than nine octaves, or why he chose to move within two intervals of octave and ninth respectively. Answering these questions following a more concise process can in many cases, paradoxically, take longer (and indeed, often you may find yourself not knowing where to start to answer). Sometimes, in fact, one might wonder why a piece was written in a certain way making the mistake of looking for an answer without considering the infinite compositional options that have been discarded: everything becomes very difficult, because without any yardstick that relativizes the choices made by the composer we find ourselves displaced in an infinite ocean of possible answers. Instead, proceeding as we have seen, we do not lose the compass and can simultaneously afford to navigate off course. The more unclear the route becomes, the greater the need for a compass and vice versa. In this way a relationship of exchange and enrichment with the composition is maintained, giving the same attention to the subjectivity and objectivity of the compositional phenomenon.

Step 5: Summarize The Deductions And Apply The Necessary Corrections

The same processes that we have followed up to this point can be put in place to analyze and reconstruct the secondary theme, the straits, the amusements etc., depending on the compositional style we have chosen. We can summarize the procedure in seven practical points (click on each issue to go back to the point of the article that contains the example):

| ① | Choose an author and a compositional model. |

| ② | Distinguish in order of importance the elements of the composition at the macrostructural level (eg. N°1 theme). |

| ③ | Evaluates the repetition behavior of rhetorical elements in the macrostructure. |

| ④ | It identifies segments with harmonic, melodic, rhythmic, growth, sound completeness. |

| ⑤ | Create a composition that conceptually mimics the model with the information you’ve gathered. |

| ⑥ | Analyze one step at a time any microstructural features of the model. |

| ⑦ | Make your composition look as similar as possible to the model using the analysis carried out. |

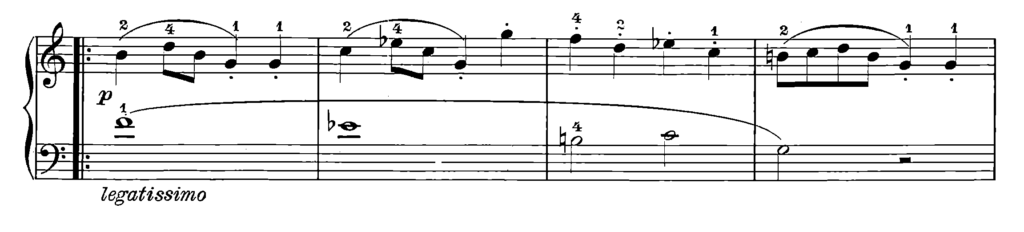

At the end of this process, the deductions we have drawn must be synthesized into theoretical models. We have done this throughout the entire article, deriving hypotheses on Clementi’s compositional choices. Exploring other compositions and compositional genres, you will gain all the tools to arrive, at some point, to have your own personal musical intuition. Here is a possible fix below:

The meter has changed, even the theme is almost completely so. However, we still notice some errors. Look at the arrows. As you can see, although now the composition looks a lot like Clementi’s original, there are still details that have not been taken into account. The highlight of the upward melody, on the G, is touched before the melody quickly descends downwards with rhythmic figures that are worth half of the larger one in the first bar. So far, everything is correct. But look at the lowest highlight, on the a: although it remains within the octave interval that we identified at the beginning, because from sol to la there is precisely a seventh, it nevertheless presents an inconsistency with respect to the original model. The inconsistency is that this lowest point is touched at a time when the composition is not going up. Beyond this error you can notice other more trivial ones: for example, the song begins with a melody that starts from the intermediary, which generally gives melodic instability to the tonic chord. Better to start on the tonic at that point where we want to lean strongly to prepare the next momentum, exactly as Clementi does.

In this version we have corrected most of our mistakes, the theme is flowing although it does not have the momentum conferred by Clementi, who moves the melody within an octave interval calculated by the tonic (while we have calculated it from the superdominant, mi-mi and not sol-sol). And yet there still remains the problem that we had already highlighted earlier, namely that we are touching several times on the culminating points in the second repetition of the theme. Clementi behaves differently, using the ninth interval to give momentum to the next section of the song. To do so, it never touches the same highlight twice. This stratagem is very useful to note, because it is one of the techniques widely used by Clementi to connect different sections of the same composition. The interval is larger than the octave within which we remained in the first section of the theme, as if to take the race from further away,

That is why I didn’t just tell you to copy the composition, but I let you write a completely free version of it. If we had not gone through this long process of deduction, now you would only know how to trace a score and you could not reason about this trivial fragment. Notice the fact that we touched the lowest point of the ninth in the second repetition of the fragment using the dominant tonality, while Clementi uses a transient alteration that had already been introduced previously (the fa diesis). This alteration clearly indicates a modulation to the near tone. As you may have studied in Harmony, many modulations that you find in the compositions of this period move within an alteration more or less than the implant key armor, according to this scheme:

| F MAJOR | C MAJOR (IMPLANT) | G MAJOR |

| D MINOR | THE MINOR | E MINOR |

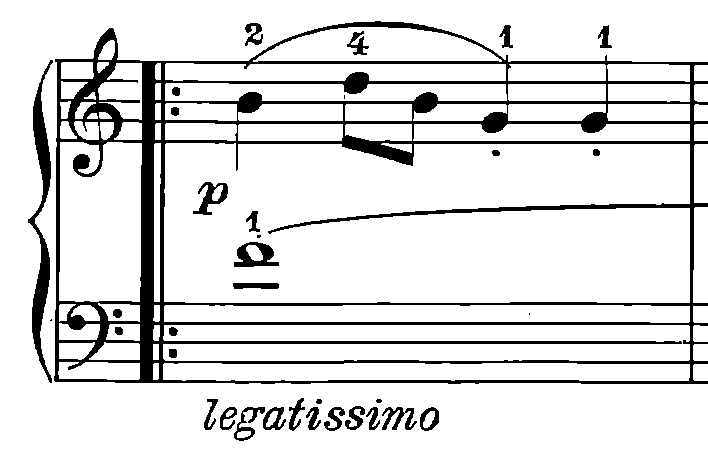

A modulation to the near tone can jump between any of these points, without distinction. Returning to Clementi, we realize that that fa diesis is introducing the key of G major because no other transient alteration of the sixth or sensitive matches the resolution so clear to the tonic as that indicated by the perfect cadence that we find in the passage:

Clementi then moved to the right in the table. In our song we are using G major as the plant tonality, so we have to move according to a different table:

| C MAJOR | G MAJOR (PLANT) | D MAJOR |

| THE MINOR | E MINOR | B MINOR |

The alteration that we must add is that of the do diesis. In our song we did not do it, moreover we did not give satisfactory confirmation to the new tonality. So let’s start from the sensitive of the new tonality, as Clementi did, using it as the lowest point of the second repetition of the theme and move from there. To do this, we must correct two other mistakes: the first, that of not having used a note as a highlight in the descending melody. The second, that of not having transposed the motif of the theme a third above as Clementi does. Let’s try to do this by staying within the interval scheme illustrated by the composer and focus on how much the choice of this precise horizon, of these precise limits upwards and downwards starting first from the tonic and then from the sensitive of the new tonality, allow us great freedom in our compositional discoveries.

So let’s proceed with the necessary corrections:

We respected the octave interval in the first repetition of the theme, moreover the two highlights on the C-sharp and the king in the second repetition of the theme were touched only once. The second engraved is transposed of the third ascendant, which now makes our passage look so much like the original fragment that someone could say if it would not have been done before to transpose it. The entire compositional process shown in this article actually has, as we have said, the precise pedagogical purpose of avoiding a poorly reasoned transposition, or the passive and mechanical tracing of a composition. I leave it to you to continue with the reconstruction of the remaining jokes, do not forget to follow the pattern you find here.

Conclusions

All the steps we followed are necessary to answer the complex initial questions and get closer to the composer’s thought: there would be many more to explore, but for the moment we stop here. Do not forget to continue to follow us, very soon we will publish new pages like this where you can learn from composers and styles always different. You can activate notifications from the banner above, or subscribe to our blog so as not to miss the next appointment, we will see you in tomorrow’s article!

- History Of The Piano – The Fortepiano - July 12, 2022

- Curt Sachs – History Of Organology At a Glance - July 8, 2022

- Giuseppe Verdi – Rigoletto, Il Trovatore, La Traviata - June 29, 2022